As might be expected, banks are the usual suspects in a banking crisis. And as quoted by the author of ‘Stress Test: Reflections on Financial Crises’:

Banks are like an economy’s circulatory system, as vital to its everyday functioning as the power grid. No economy can grow without a financial system that works, safeguarding the savings of individuals, moving money where it’s needed, and helping families and businesses invest in their futures. And ours was still a mess.”

Timothy Geithner

Lending long-term whilst borrowing short-term is the typical dynamic of a commercial bank. It takes deposits from the public with the promise of keeping them safe and lends them out for a longer period in exchange for a return. Seems easy enough to understand. So, how do financial crises occur with these organisations at the centre of the action?

In this article, we will explore three factors that contribute to a financial crisis:

Dependency on short-term capital for growth: This refers to the reliance on easily obtainable short-term funds to fuel economic expansion. When a significant portion of capital comes from short-term sources, such as loans or investments that require quick repayment, it can create vulnerability in the event of a financial crisis.

Credit booms, high household debt and leverage: The easy availability of capital during prosperous times often leads to a surge in borrowing, lending activities and high leverage. This credit boom can result in households accumulating high levels of potentially very risky debt and in institutions exploiting leverage (many times exceeding 100%). Consequently, when a financial crisis occurs, it exposes the participants to risks such as rising interest rates (reflecting increasing risk and affecting their capacity to pay back), margin calls and capital runs, where investors quickly withdraw their funds, putting further strain on the economy.

Local currency pegged to another currency (typically found in Emerging Markets): Some economies, particularly those classified as emerging markets, have their local currencies tied or pegged to another currency, usually a stronger and more stable one. Once capital starts to “run” and foreign investors withdraw their money, the local currency might end up under significant pressure.

The three points above do not need to all happen together (every crisis has its idiosyncrasies); however, they can help paint a picture of what can happen during a financial crisis.

What is the sequence of events in a financial crisis?

-Institutions start lending out money at a higher pace, “borrowing” mainly from international investors that see an opportunity for growth. (Runnable capital enters the country)

-Initial investments yield good results which fuel more lending and the expansion to a Credit Boom mentality

-The system falls complacent, people and institutions take on riskier investments, thinking good-times will remain good indefinitely and risk assessments start to fall down the sidelines. (Remember anyone telling you that London property prices always go up? This is untrue of any asset, and an example of such complacency.)

-With a lax risk assessment, credit becomes more available for people with an increased risk of not being able to pay back.

-As payments start to fall back, “bad loans”, known as impairments, start increasing in the financial institutions’ books which starts foreshadowing instability.

-As the instability increases, people start withdrawing deposits; liquidity drops, choking a financial system that finds itself already overstretched, reinforcing the cycle. (Runnable capital starts to run!)

-If the currency of the country in question is pegged to the world currency (which is the USD roughly after WWII), the exit of foreign investment would put pressure on the exchange. To maintain the peg the government will need to use their central authority power to control the variation. This will most likely mean that they will end up dramatically reducing their savings in foreign currency (which again creates more instability and can spark certain anxiety in their population). Once the peg is abandoned, the country will find itself in a recession: depleted savings, many people unable to pay loans (short and long term), corporations unable to take loans as the financial system stumbles and foreclosures starting to show up pushing unemployment. As a side note, such pegs have historically not been exclusive to emerging markets. Sterling was pegged to the value of European currencies in 1990, with disastrous effects when it dropped 19% on Black Wednesday, and the Swiss Franc was capped against the value of the Euro until 2015 when its removal caused the currency to spike 30% in a day.

The above is a harsh picture that comes from a simple model. It is important to note that credit itself is not inherently bad, as it enables individuals to invest and improve their quality of life. Important to note: Financial crises are often preceded by asset and credit booms but not every credit boom creates a crisis.

We have seen this sort of sequence of events develop more than once with crises like Mexico in the 90s (the so-called “Tequila Effect”) and Asian Crisis, which started with the events that unravelled in Thailand in 1997.

Consumer Credit and Household Debt

Consumer credit is defined as “Credit extended to individuals for household, family, and other personal expenditures, excluding loans secured by real estate.” This means personal loans that are provided to buy goods and/or services.

This is further broken down into “Revolving” and “Non-Revolving” credit. Revolving credit does not have a predetermined expiration date. The most common example is a credit card. Non-revolving credit, by contrast, has specific dates and payment schedules. It is typically used for specific purposes like financing a car, purchasing a home (mortgages), or funding higher education (student loans). Non-revolving credit is often provided in a lump sum, and you repay it in instalments over a fixed period of time, according to a predetermined schedule.

Revolving credit (e.g. credit cards) is typically seen as short term, whilst non-revolving (e.g. student loans, mortgages, etc) are typically long term.

A brief history of credit in the US

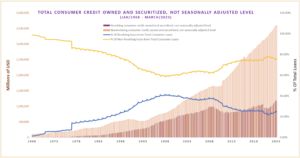

From 1968 to roughly 1997, revolving loans (short-term loans, blue line) consistently increased, peaking at 41.47% of the total loans value by December 1998. By mid-2007, although not at thier highest, they still accounted for approximately 37%.

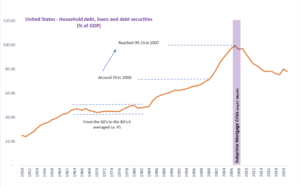

It is important to consider the total household debt (~$4.79tr by the end of March 2023, represented by the vertical bars) in relation to the GDP which we present in the chart below.

In the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, credit was liberally extended to so-called subprime borrowers, whose credit ratings were poor. This led to the Subprime Mortgage Crisis, in which US regulators took extraordinary efforts where the FED, the Treasury and the FDIC worked together. They ultimately succeeded, leading to a faster recovery compared to other countries.

As with other crises, studies of the events have shown clear vulnerabilities, some of which were discussed above:

-Credit boom and high consumer exposure

-Complacency within the system

-Insufficient risk analysis

However, this crisis also had specific issues related to the US economy, such as the expansion of what came to be known as Shadow Banking and the growth of securitisation through instruments like Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS), whose underlying structures were often poorly understood by investors.

In 2017, the IMF highlighted that while increasing household debt may initially stimulate the economy in the short term, the effects reverse in the following years (around 3-5 years) as debt accumulates and people reduce spending to repay loans. This creates a vulnerable situation with an increasing likelihood of a crisis.

Debt on a global scale

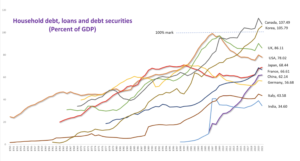

What does debt look like for the world’s top 10 economies? This chart shows household debt, loans and debt securities as a percentage of GDP amongst these countries.

It is worth noting that both Canada and Korea have household debt-to-GDP ratios above 100%, according to the latest available data. However, what stands out even more, is the remarkable growth in Korea, with its household Debt/GDP ratio increasing 84% of the time (50 times within 59 data points) and the abrupt jump for India.

While the data is limited, China’s reported household debt has increased every year since 2006. It currently holds at around 62.14%, slightly below the median among the top 10 economies.

Debt in the UK

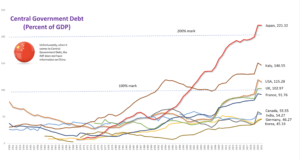

The UK is ranked as the 6th largest economy by GDP globally. It ranks third in household debt among the top 10 economies and its government debt ended 2021 slightly above 100% of GDP.

The UK is currently a net borrower in terms of its overall balance, indicating a reliance on international capital.

There are a few important points to note:

-As illustrated in the chart in “Debt on a Global Scale”, despite a spike in 2020, household debt appears to be decreasing although it remains high.

-Central Government debt has followed a similar path to other European nations like France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Ireland. Furthermore, it remains below economies like Greece, Italy and Portugal.

-The Net borrowing positions fluctuate quite heavily. After a sharp decline in 2020, the UK position seems to be recovering.

Where do we go from here?

In conclusion, credit plays a crucial role in banking crises, as evidenced by historical events and current economic indicators.

Credit creates opportunities for households and businesses, however, credit booms and excessive household debt can contribute to the vulnerability of an economy during a crisis.

Examining the case of the US, the Subprime Mortgage Crisis highlighted vulnerabilities such as a credit boom, high consumer exposure, complacency within the system, and insufficient risk analysis. Aggressive actions by regulators helped mitigate the crisis and expedite recovery.

Overall, understanding the role of credit and its associated risks is crucial in preventing and managing banking crises. Prudent risk assessment, regulatory oversight, and responsible lending practices are essential for maintaining financial stability and mitigating the negative impacts of credit-related crises.